Reactions of MoCl5 with Succinimide, Imidazole, 3-Methylpyridine and 4-Methylpyridine in THF

Rakesh Kumar1 and Gursharan Singh2*

1Punjab Technical University, Kapurthala India.

2Department of Applied Chemistry, GianiZail Singh Campus College of Engineering and Technology, Dabwali Road, MRSPTU Bathinda-151001-India.

Corresponding Author E-mail: gursharans82@gmail.com

DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/ojc/370316

Article Received on : 01-Apr-2021

Article Accepted on :

Article Published : 24 May 2021

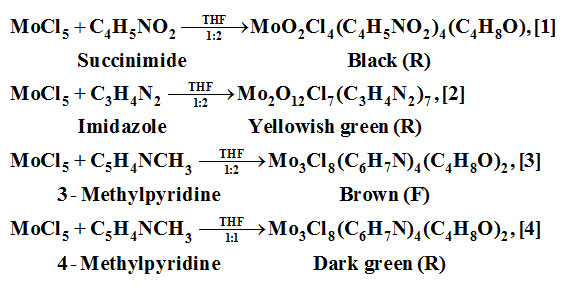

MoCl5 was reacted with succinimide/imidazole/3-methylpyridine/4-methylpyridine in THF medium using equal/double molar concentrations of the ligand at room temperature. The end products obtained are: MoO2Cl4(C4H5NO2)4(C4H8O), [1]; Mo2O12Cl7(C3H4N2)7, [2]; Mo2O12Cl7(C3H4N2)7, [3]and Mo3Cl8(C6H7N)4(C4H8O)2, [4].

The above compounds were characterized by FTIR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, LC-MS, microbiological and C, H, N, Mo, Cl studies. All procedures and work outs were handled in vacuum line using dry nitrogen atmosphere to protect the products from oxidation/hydrolysis by air/moisture.Elemental data and fragments visualized in LC-MS are concordant with the formulae derived.

| Copy the following to cite this article: Kumar R, Singh G. Reactions of MoCl5 with Succinimide, Imidazole, 3-Methylpyridine and 4-Methylpyridine in THF. Orient J Chem 2021;37(3). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Kumar R, Singh G. Reactions of MoCl5 with Succinimide, Imidazole, 3-Methylpyridine and 4-Methylpyridine in THF. Orient J Chem 2021;37(3). Available from: https://bit.ly/3oHDQn2 |

Introduction

Succinimide

Succinimides1 are used as precursors for biological applications. Succinimide is a part of various biologically active molecules having properties: antitumour2, CNS depressant3, anorectic4, hypotensive5, analgesic6, cytostatic7, nerve conduction blocking8, antispasmodic9, bacteriostatic10, muscle relaxant11, antibacterial12, antifungal13, anti-convulsant14 and anti-tubercular15.

Imidazole

Imidazole containing drugs are used16-28 as:anticoagulants, 20-carboxypeptidaseinhibitors,antifungal, β-lactamase inhibitors,hemeoxygenase inhibitors, anticancer, antitubercular, anti-inflammatory,antibacterial, antiviral, antidiabetic HETE (20-Hydroxy-5,8,11,14-eicosatetraenoic acid) synthase inhibitors, antimalarial and antiaging agents.

3-Methylpyridine

3-Methylpyridine29 is used to prepare agrochemical chlorpyrifos30. As compared to 2-methylpyridine/4-methylpyridine31, 32 there is low degradation andpoor volatility of 3-methylpyridine from water samples.3-Methylpyridine is used as an antidote for organophosphate poisoning 33. It is biodegradable.

4-Methylpyridine

Many heterocyclic compounds can be prepared from 4-methylpyridine34. It is a precursor to other commercially significant species, often of medicinal interest. 4-Methylpyridine is a precursor for the preparation of the antituberculosis drug35 ‘isoniazid’. It is very reliable and commonly used medicine for tuberculosis.

It has been noted that many drugs havegreater activity as metal chelates as compared to organic compounds36-41.

Aim of Investigation

Molybdenum(V) chloride has been reported to react with a variety of N-heterocyclic bases.Many reactions of aromatic azoles, diaminoalkanes, imides, 4-phenylimidazole-2-thiol, alkylpyridines, 2-thiazoline-2-thiol, mercaptopyridine-N-oxide sodiumand thiols with MoCl5 have been studied42-47 by the author.

In view of the fact that complexes of these bases with transition metalsshow various applications. Complexes of succinimide, imidazole, 3-methylpyridine and 4-methylpyridine with MoCl5 have been synthesized and studied.Characterization of these complexes was executed with 1H NMR, 13 C NMR, FTIR, LC-MS, microbiological studies and elemental analysis.

Materials and Methods

Succinimide, imidazole, 3-methylpyridine, 4-methylpyridine and MoCl5were bought fromSigma-Aldrich.

The products are easily oxidized/hydrolysed by air/moisture, so all procedures and work outs were handled in vacuum line using dry nitrogen atmosphere to protect the products from oxidation/hydrolysis by air/moisture.

Ligand dissolvedin dry THF was combined from dropping funnel withMoCl5dropwise with continuous agitation. The reaction was carried outfor 7-8 h.Filtration unit fitted with G-4 sintered glass crucible was used for filtration and isolation of products.

Molybdenum analysis was performed by oxinate method gravimetrically48. Chlorine analysis was performed by silver chloride method gravimetrically48.Thermo Finnigan Elemental Analyser was used for analysis of remaining elements. Perkin-Elmer 400 FTIR Spectrometer was used for obtaining vibrational spectra.1H/13C nuclear magnetic resonancespectrain DMSO-d6 were obtainedwithMultinuclear BruckerAvance-II 400 NMR spectrometer. LC-MS spectra were obtainedin the range 0 – 1100 m/z. Above instruments were used atP. U. Chandigarh.

Antibacterial and antifungal activities of molybdenum compounds synthesized were tested using strains: gram positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus (MTCC-737), gram negative bacteria E. coli (MTCC-1687), fungi Candida albicans (MTCC-227) and Aspergillusniger (MTCC-282). Agar well diffusion assay method was used.Standard drug (amoxicillin) for bacteria and standard drug (ketoconazole) for virus as reference were used.MTCC (The Microbial Type Culture Collection and Gene Bank, Chandigarh, India) cultures were used. Testing was carried out at ISF Analytical Laboratory (ISF College of Pharmacy), Ferozepur Road, Moga, Punjab, India.

Reactions

(R)/(F) represent the product source,

Results and Discussions

Elemental Analysis

Table 1: reveals the percentage of the observed (theoretical) values of the elements.

|

(Elemental Analysis) |

|||||

|

Compounds |

Cl |

Mo |

H |

C |

N |

|

MoO2Cl4(C4H5NO2)4(C4H8O), [1] (Black/738.0) |

18.77 (19.24) |

12.10 (13.00) |

02.57 (03.25) |

32.37 (32.52) |

06.85 (07.58) |

|

Mo2O12Cl7(C3H4N2)7, [2] (Yellowish green/1108.5) |

21.78 (22.41) |

16.93 (17.32) |

02.81 (02.52) |

22.28 (22.73) |

17.01 (17.68) |

|

Mo3Cl8(C6H7N)4(C4H8O)2, [3] (Brown/1088.0) |

25.57 (26.10) |

25.53 (26.47) |

03.88 (04.04) |

36.07 (35.29) |

04.68 (05.14) |

|

Mo3Cl8(C6H7N)4(C4H8O)2, [4] (Dark green/1088.0) |

25.33 (26.10) |

25.97 (26.47) |

03.49 (04.04) |

34.67 (35.29) |

04.53 (05.14) |

FTIR Spectra

Succinimide49, 50 has N-H stretching at 3411 cm-1 & 3222 cm-1. Band at 3434 cm-1 suggests presence of N-H group in [1]. Stretching at 938 cm-1 and 918 cm-1 reveal the existence of cis-MoO22+ core51, 52 in [1]. C=O frequency has not altered much from 1773 cm-1 and 1711 cm-1, indicating there by absence of Mo–O coordination in [1]. There seems to be little decrease in C=O bond order (Table-2).

Table 2: FTIR absorptions in cm−1

|

Table 2: (FTIR absorptions in cm−1) |

||

|

Assignments |

Succinimide49, 50 |

[1] |

|

N-H str. |

3411 s, b, 3222 s, b |

3434.0 s, b |

|

CH2 sym. str. |

2962, 2946 w |

|

|

C=O sym., H-N-C in plane bending |

1773 m |

1773.5 sh |

|

C=O asym., H-N-C in plane bending |

1711 vs, b |

1706.1 s |

|

CH2 sym. scissoring |

1432 m |

1425.9 sh |

|

CH2asym. scissoring |

1402 m |

|

|

C-N-C asym. str., H-N-C in plane bending |

1348 s, 1335 |

1371.8 m |

|

CH2 bending, ring in plane bending |

1296 s |

1298.1 m |

|

CH2 bending |

1242 |

1247.3 sh |

|

C-N-C asym. str., H-N-C in plane bending |

1188 s, |

1190.3 s |

|

C-C str., CNC sym. str. |

850 |

853.5 sh |

|

CH2 bending, ring out of plane bending |

818 s |

818.0 w |

|

OCN asym. out of plane bending |

631 m |

643.3 m |

|

OCN sym. out of plane bending, CH2 bending |

541 w |

556.3 sh |

|

Mo-N str. |

|

416.7 w |

|

Mo=O Str. of cis-MoO22+ core51, 52 |

|

938.2 w, 918.1 sh |

It is reported that N-H stretching of imidazole53, 54 appears at 3722 cm-1-3272 cm-1. There is presence of broad band at 3431 cm-1-3000 cm-1 pertaining to N-H group in [2]. This broadening occurs in the solid state (KBr disk) because of hydrogen bonding. A strong band at 975 cm-1 is suggestive of terminal Mo=O51, 55, 56 in [2] (Table-3).

Table 3: FTIR absorptions in cm−1

|

Table 3: (FTIR absorptions in cm−1) |

||

|

Assignments |

Imidazole53, 54 |

[2] |

|

N-H str. |

3722 vb, 3657 vb, 3272, 3242, 3238 |

3431.1vs, 3000 s, vvb |

|

C-H str. |

3195, 3166 |

3157.8sh, 2997.0sh |

|

C=C ring str. |

1560, 1502 |

1633.2 s, 1592.5sh |

|

N-C ring str. |

1435 |

1445.4 w |

|

C-H in plane bending |

1094, 1073 |

1194.1 w, 1079.9 w |

|

C-H out of plane bending (wagging), Ring twisting |

817, 728 |

760.7 m |

|

Ring twisting |

648 |

627.3 m |

|

Ring twisting, N-H wagging |

527 |

|

|

Terminal Mo=O51, 55, 56str. |

|

975.2 m |

C-H ring stretching of 3-methylpyridine57-60 appears at 3062 cm-1 and 3031 cm-1. Band at 3055 cm-1 has been located in [3]. There is increase of ring C=N str.&ring C=N torsion values and decrease of ring C-H bending mode values, which show presence of some Mo(dπ)→N(pπ) back bonding. A strong band at 977 cm-1 is suggestive of terminal Mo=O45, 49, 50 in [3] (Table-4).

Table 4: FTIR absorptions in cm−1

|

Table 4: (FTIR absorptions in cm−1) |

||

|

Assignments |

3-Methylpyridine57-60 |

[3] |

|

C-H Ringstr. |

3062, 3031 |

3397.2 s, 3055.8sh |

|

C-H Methylstr. |

3000, 2959, 2926 |

2867.8 sh |

|

Ringstr. |

1598, 1579 |

1630.5 m, 1552.7 m |

|

Ring C-H bending |

1480 |

|

|

C-H Methyl assym bending |

1457, 1450 |

1469.5 m |

|

Ring C-Hbending |

1416 |

|

|

C-H methylsym. bending |

1386 |

1384.8 w |

|

Ring C-Hbending |

1363 |

1304.38 sh |

|

Ring str. |

1249 |

1263.4 w |

|

C-C bond between ring and methylstr. |

1229 |

|

|

Ring C-H bending |

1192 |

1185.3sh |

|

C-H methyl rocking |

1126, 1045 |

1116.25 m |

|

Ring out of plane bending |

1031 |

1044.32 w, 1027.32 w |

|

RingC=N str. |

791 |

890.5 vs, 785.3 m, 737.4 |

|

RingC=N torsion |

712 |

723.6 m |

|

Ring bending |

636, 538 |

676.7 m, 511.9 w |

|

∂ C-C bond between ring and methyl |

456 |

464.2 w |

|

Terminal Mo=O45, 49, 50str. |

|

977.0 w |

C-H ring stretching of 4-methylpyridine 53-60 appears at 3074 cm-1 and 3032 cm-1. Band at 3097 cm-1 has been located in [4]. There is increase of ring C=N str.&ring C=N torsion values and decrease of ring C-H bending mode values, which show presence of some Mo(dπ)→N(pπ) back bonding. A strong band at 976 cm-1 is suggestive of terminal Mo=O 45, 49, 50 in [4] (Table-5).

Table 5: (FTIR absorptions in cm−1)

|

Table 5: (FTIR absorptions in cm−1) |

||

|

Assignment |

4-Methylpyridine57-60 |

[4] |

|

C-H Ringstr. |

3074, 3032 |

3400.9 vs, b, 3097.5 sh |

|

C-H Methylstr. |

2992, 2926 |

2948.8 sh |

|

Ringstr. |

1610, 1563 |

1640.3 s, 1508.0m |

|

Ring C-H bending |

1501 |

|

|

C-H Methyl assym bending |

1458, 1445 |

1444.7 sh |

|

Ring C-H bending |

1418 |

|

|

C-H methyl sym. bending |

1383 |

1379.6 w |

|

Ring C-H bending |

1365 |

1316.0 w |

|

Ring str. |

1227 |

1256.0 w |

|

C-C bond between ring and methyl str. |

1210 |

1204.0 w |

|

Ring C-H bending |

1194 |

|

|

C-H Methyl rocking |

1114, 1072 |

1113.4 w, 1039.6 w |

|

Ringout of plane bending |

995, 875 |

|

|

Ring C=N str. |

730 |

793.8 m, 738.0 m |

|

Ring C=N torsion |

524 |

569.1 sh |

|

∂ C-C bond between ring and methyl |

486 |

476.5 w |

|

Terminal Mo=O45, 49, 50str. |

|

976.1s |

1H NMR Spectra

CH2 peaks of succinimide61, 62 absorb at 2.74 ppm. 1H NMR of [1] in DMSO-d6 shows CH2 peaks at 2.63 ppm showing upfield shift (Table-6). ↑ and ↓ represent upfield/downfield shift.

Table 6: (1H NMR absorptions in ppm)

|

Table 6: (1H NMR absorptions in ppm) |

||

|

Assignments |

Succinimide61, 62 in CDCl3 |

[1] |

|

N-H |

8.9 |

11.12 ↓ |

|

CH2 |

2.75 |

2.63↑ |

|

Residual63 DMSO-d6 |

|

2.57 |

|

THF63 C-2, 5 |

|

3.51 |

|

THF63 C-3, 4 |

|

|

Imidazole 64, 65 spectrumin shows C-H proton (in middle ofnitrogen atoms) absorption at 7.72 ppm.Remaining C-H protons absorb at 7.14 ppm. N-H absorption occurs at 11.60 ppm. Spectrum of [2] in DMSO-d6 shows relatively downfield absorptions for all the protons due to coordination of ligand lone pairs with Mo cations (Table-7). Two equivalent C–H protons of imidazole appear as singlets, because of the tautomerization equilibrium.

Table 7: (1H NMR absorptions in ppm)

|

Table 7: (1H NMR absorptions in ppm) |

||

|

Assignments |

Imidazole64, 65 in CDCl3 |

[2] |

|

N-H |

11.60 1H |

14.94 (b) 2H ↓ |

|

C-H (in middle of nitrogen atoms) |

7.72 1H |

9.21 (s) 1H ↓ |

|

C-H (remaining) |

7.14 2H |

7.74 (s) 2H ↓ |

|

Residual63 DMSO-d6 |

|

2.58 (s) |

|

THF63 C-2, 5 |

|

3.63 (s) 4H |

|

THF63 C-3, 4 |

|

|

On comparison of 1H NMR of 3-methylpyridine 58, 59, 66 with that of [3], it is observed that these absorptions have moved downfield due to decrease in π-electron density of the ring on lone pair sharing bynitrogen with molybdenum cation (Table-8).

Table 8: (1H NMR absorptions in ppm)

|

Table 8: (1H NMR absorptions in ppm) |

||

|

Absorptions |

3-Methylpyridine58, 59, 66 in CDCl3 |

[3] |

|

H (CH3) |

2.32 3H Singlet |

2.57 ↓ |

|

H-C1 |

8.44 1H Singlet |

8.891H ↓ |

|

H-C3 |

7.45 1H Doublet |

8.47 1H ↓ |

|

H-C4 |

7.16 1H Triplet |

8.01 ↓ |

|

H-C5 |

8.42 1H Doublet |

8.83↓ |

|

Residual63 DMSO-d6 |

2.58 |

|

|

THF64 C-2, 5 |

3.65 |

|

|

THF65 C-3, 4 |

1.56 |

|

On comparison of 1H NMR of 4-methylpyridine 58, 59, 66 with that of [4]it is observed that these absorptions have moved downfield due to decrease in π-electron density of the ring on lone pair sharing by nitrogen with molybdenum cation(Table-9).

Table 9: (1H NMR absorptions in ppm)

|

Table 9: (1H NMR absorptions in ppm) |

||

|

Assignments |

4-Methylpyridine58, 59, 66 in CDCl3 |

[4] |

|

H (CH3) |

2.34 3H s |

2.58↓ |

|

H-C1& H-C5 |

8.46 2H d |

8.78↓ |

|

H-C2 & H-C4 |

7.10 2H d |

7.88↓ |

|

Residual63 DMSO-d6 |

|

2.50 |

|

THF63 C-2, 5 |

|

3.32 |

|

THF63 C-3, 4 |

|

1.49 |

13C NMR Spectra

On comparison of 13C NMR of succinimide67 with that of [1], it is observed that these absorptions have moved slightly upfield (Table-10).

Table 10: (13C NMR absorptions in ppm)

|

Table 10: (13C NMR absorptions in ppm) |

||

|

Assignments |

Succinimide67 |

[1] |

|

C attached to oxygen |

183.85 |

179.30 singlet ↑ |

|

Other C |

30.30 |

29.41 singlet ↑ |

|

Residual68 DMSO-d6 |

|

39.37 pentet ↑ |

|

THF69 C-2, 5 |

|

|

|

THF69 C-3, 4 |

|

|

Microbiological Activity

Molybdenum compounds prepared were tested for their antibacterial and antifungal activities with strains: gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus (MTCC-737), gram-negative bacteria E. coli (MTCC-1687), fungi Candida albicans (MTCC-227) and Aspergil lusniger (MTCC-282).Reference drugs amoxicillin and ketoconazole were used for bacteria and fungi, respectively. Zone of inhibition70 for a strain of bacteria/fungi has been measured to find out extent of resistance of bacteria/fungi to the reference drug.Molybdenum compounds have been observed potentially active against bacteria and fungi (Table-11).Especially,

Compounds 1, 2, 3 and 4 have greater antibacterial potential against E. coli than the reference drug (amoxicillin).

Compounds 3 and 4 have greater antifungal potential against C. albicansthan the reference drug (ketoconazole).

Table 11: (Microbiological Study)

|

Table 11: (MicrobiologicalStudy) |

||||

|

Compound(100 µg/ml) |

Zone of inhibition63(mm) |

|||

|

Gram- positive |

Gram- negative |

Antifungal |

||

|

S. aureus |

E. coli |

C. albicans |

A. niger |

|

|

Reference Drug |

25.69 |

18.35 |

21.37 |

28.21 |

|

[1] |

21.38 |

19.51 |

18.54 |

21.29 |

|

[2] |

18.63 |

21.41 |

19.66 |

22.51 |

|

[3] |

21.41 |

21.36 |

22.57 |

19.12 |

|

[4] |

19.36 |

21.58 |

22.32 |

18.74 |

|

Solvent control |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Conclusion and results |

These compounds can kill and inhibit the growth of microbes |

|||

Mass Spectra (LC-MS)71

Ionic speciesnoted (Tables-12, 13)justify the formulae,

|

Table 12: (LC-MS Ionization) Click here to View table |

Table 13: (LC-MS Ion m/z values)

|

Table 13: (LC-MS Ion m/z values) |

||||

|

Comp. |

Ion |

Calculated71 |

Detected |

Relative intensity |

|

[1] |

[MoO2Cl4(C4H8O)(C4H5NO2)3]2+ |

319.46 |

321.11 |

15 |

|

[MoO2Cl4(C4H8O)(C4H5NO2)4]+ |

737.95 |

737.54 |

2% |

|

|

[MoOCl4(C4H8O)]+ |

325.83 |

327.11 |

42% |

|

|

[MoOCl2(C4H5NO2)2(C4H8O)]2+ |

226.97 |

230.07 |

36% |

|

|

[C4H5NO2]+ |

99.03 |

100.05 |

52 |

|

|

[C4H8O]+ |

72.05 |

73.07 |

13 |

|

|

[MoOCl2]2+ |

91.91 |

91.04 |

100 |

|

|

[MoO2Cl4(C4H8O)]2+ |

170.91 |

172.11 |

8% |

|

|

[2] |

[Mo2O12Cl7(C3H4N2)7]2+ |

554.40 |

555.38 |

|

|

[Mo2O4Cl6(C3H4N2)6]2+ |

438.91 |

440.05 |

7% |

|

|

[Mo2O4Cl2(C3H4N2)6]2+ |

368.97 |

371.99 |

12% |

|

|

[Mo2O4Cl2(C3H4N2)4]2+ |

300.93 |

303.94 |

3% |

|

|

[Mo2O4Cl2(C3H4N2)2]2+ |

232.90 |

235.18 |

2% |

|

|

[Mo2O4Cl2]2+ |

164.86 |

163.10 |

8% |

|

|

[MoOCl2]2+ |

91.91 |

91.04 |

10 |

|

|

[C3H4N2]+ |

68.03 |

69.04 |

100 |

|

|

[3] |

[Mo3Cl8(C6H7N)4(C4H8O)2]2+ |

544.90 |

544.46 |

3% |

|

[Mo3Cl8)(C6H7N)4]2+ |

472.84 |

472.39 |

4 |

|

|

[MoCl6)(C6H7N)]+ |

400.77 |

400.32 |

5% |

|

|

[MoCl4)(C6H7N)]+ |

330.83 |

328.25 |

10% |

|

|

[C6H7N]+ |

93.05 |

94.06 |

100 |

|

|

[C4H8O]+ |

72.05 |

73.07 |

8 |

|

|

[4] |

[Mo3Cl8(C6H7N)4(C4H8O)2]2+ |

544.90 |

544.47 |

6% |

|

[Mo3Cl8)(C6H7N)4]2+ |

472.84 |

472.39 |

8% |

|

|

[MoCl6)(C6H7N)]+ |

400.77 |

400.32 |

18% |

|

|

[MoCl4)(C6H7N)]+ |

330.83 |

328.26 |

18% |

|

|

[C6H7N]+ |

93.05 |

94.06 |

100% |

|

|

[C4H8O]+ |

72.05 |

73.07 |

3% |

|

Conclusion

Band at 3434 cm-1 suggests the presence of N-H group in [1]. Stretching at 938 cm-1 and 918 cm-1 reveal the existence of cis-MoO22+ corein [1]. C=O frequency has not altered much from 1773 cm-1 and 1711 cm-1, indicating thereby absence of Mo–O coordination in [1]. There seems to be little decrease in C=O bond order. 1H NMR of [1]shows CH2 peaks at 2.63 ppm showing up field shift.13 C NMR of [1] shows that the absorptions have moved slightly up field. Compound is potentially active against microbes. Detection of ions in LC-MS are in tune with the formula presented.

There is presence of broad band at 3431 cm-1-3000 cm-1 pertaining to N-H group in [2]. This broadening occurs in the solid state (KBr disk) because of hydrogen bonding. A strong band at 975 cm-1 is suggestive of terminal Mo=O in [2]. Imidazole spectrum shows C-H proton (in middle of nitrogen atoms) absorption at 7.72 ppm. Remaining C-H protons absorb at 7.14 ppm. N-H absorption occurs at 11.60 ppm. Spectrum of [2] shows relatively downfield absorptions for all the protons due to coordination of ligand lone pairs with Mo cations. Two equivalent C–H protons of imidazole appear as singlets because of the tautomerization equilibrium. Compound is potentially active against microbes.Detection of ions in LC-MS are in tune with the formula presented.

Band at 3055 cm-1 has been located in [3]. There is increase of ring C=N str. and ring C=N torsion values and decrease of ring C-H bending mode values, which show presence of some Mo(dπ)→N(pπ) back bonding. A strong b and at 977 cm-1 is suggestive of terminal Mo=O in [3]. It is observed that these proton absorptions have moved downfield due to decrease in π-electron density of the ring on lone pair coordination by nitrogen with molybdenum cation.Compound is potentially active against microbes.Detection of ions in LC-MS are in tune with the formula presented.

Band at 3097 cm-1 has been located in [4]. There is increase of ring C=N str. and ring C=N torsion values and decrease of ring C-H bending mode values, which show presence of some Mo(dπ)→N(pπ) back bonding. A strong band at 976 cm-1 is suggestive of terminal Mo=O in [4]. It is observed that these proton absorptions have moved downfield due to decrease in π-electron density of the ring on lone pair coordination by nitrogen with molybdenum cation.Compound is potentially active against microbes.Detection of ions in LC-MS are in tune with the formula presented.

Acknowledgement

P. U. Chandigarh, India is acknowledged for providing characterizing facility.

Conflict of Interest

Authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- Shetgiri, N.P.;Nayak,B.K.,Indian J. Chem., 2005, 44B, 1933-1936.

- Hall, I. H.; Wong, O. T.; Scovill, J. P.,Biomed Pharmacother,1995, 49(5), 251-258.

CrossRef - Aeberli, P; Go gerty, J. H; Houlihan, W. J; Iorio, L. C.,J. Med. Chem.,1976, 19(3), 436-438.

CrossRef - Rich, D. H.; Gardner, J. H.,Tetrahedron Letters, 1983, 24(48), 5305-5308.

CrossRef - Pennington, F. C.; Guercio, P. A.; Solomons, I. A.,J. Amer. Chem. Soc., 1953, 75(9), 2261.

CrossRef - Correa, R.; Filho, V. C.; Rosa, P. W.; Pereira, C. I.; Schlemper, V.; Nunes, R. J.,Pharm. Pharmacol. Comm., 1997, 3(2), 67-71.

- Crider, A. M; Kolczynski, T. M.; Yates, K. M., J. Med. Chem.,1980, 23(3), 324-326.

CrossRef - Kaczorowski, G. J.; McManus, O. B.; Priest, B. T.; Garcia, M. L., Gen. Physiology, 2008, 131(5), 399-405.

CrossRef - Filho, V. C.; Nunes, R. J.; Calixto, J. B.; Yunes, R. A., Pharm. Pharmacol. Comm., 1995,1(8), 399-401.

- Johnston, T. P.; Piper, J. R.; Stringfellow, C. R.,J. Med. Chem.,1971, 14(4), 350-354.

CrossRef - Musso, D. L.; Cochran, F. R.; Kelley, J. L.; McLean, E. W.; Selph, J. L.; Rigdon, G. C., J. Med. Chem., 2003, 46(3), 399-408.

CrossRef - Zentz, F.; Valla, A.; Guillou, R. L.; Labia, R.; Mathot, A. G.; Sirot, D.,Farmaco, 2002, 57(5), 421-426.

CrossRef - Hazra, B. G.; Pore, V. S.; Day, S. K.; Datta, S.; Darokar, M. P., Saikia, D.,Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett., 2004, 14(3), 773-777.

CrossRef - Kornet, M. J.; Crider, A. M.; Magarian, E. O., J. Med. Chem., 1977, 20(3), 405-409.

CrossRef - Isaka, M.; Prathumpai, W.; Wongsa, P.; Tanticharoen, M.; Hirsutellone, F.,Org. Lett.,2006, 8(13), 2815-2817.

CrossRef - Katritzky, A. R.; Rees,Comprehensive Heterocyclic Chemistry, 1984, 5, 469-498.

CrossRef - Grimmett, M. R., Imidazole and Benzimidazole Synthesis, Academic Press, 1997.

CrossRef - Brown, E.G., Ring Nitrogen and Key Biomolecules, Kluwer Academic Press, 1998.

- Pozharskii, A.F., Soldatenkov, A. T.; Katritzky,A. R.,Heterocycles in Life and Society, John Wiley & Sons, 1997.

- Gilchrist, T. L., Heterocyclic Chemistry,the Bath Press,1985, ISBN 0-582-01421-2.

- Congiu, C.;Cocco, M. T.;Onnis, V.,Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 2008, 18, 989–993.

- Venkatesan, A.M.;Agarwal, A.;Abe, T.;Ushirogochi, H.O.;Santos, D.;Li, Z.;Francisco, G.;Lin, Y.I.;Peterson, P.J.;Yang, Y.;Weiss, W.J.;Shales, D.M.;Mansour, T.S.,Bioorg. Med. Chem., 2008, 16, 1890-1902.

CrossRef - Nakamura, T.;Kakinuma, H.;Umemiya, H.;Amada, H.;Miyata, N.;Taniguchi, K.;Bando, K.;Sato, M.,Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 2004, 14, 333-336.

CrossRef - Han, M. S.; Kim, D. H., Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 2001, 11, 1425- 1427.

CrossRef - Roman, G.;Riley, J.G.;Vlahakis, J. Z.;Kinobe, R.T.;Brien, J.F.;Nakatsu, K.;Szarek,W.A., Bioorg. Med. Chem., 2007, 15, 3225-3234.

CrossRef - Bbizhayev, M. A., Life Sci., 2006, 78, 2343-2357.

CrossRef - Nantermet, P.G.;Barrow, J.C.;Lindsley, S.R.;Young, M.;Mao, S.;Carroll, S.;Bailey, C.;Bosserman, M.;Colussi, D.;McMasters, D.R.;Vacca, J.P.;Selnick, H.G.,Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.,2004, 14, 2141-2145.

CrossRef - Adams, J. L.;Boehm, J.C.;Gallagher, T. F.;Kassis, S.;Webb, E. F.;Hall, R.;Sorenson, M.; Garigipati, R.;Griswold, D. E.; Lee,J. C.,Bioorg.Med. Chem.Lett., 2001,11,2867-2870.

CrossRef - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/3-Methylpyridine.

CrossRef - Shimizu, S.;Watanabe, N.;Kataoka, T.;Shoji, T.;Abe, N.;Morishita, S.;Ichimura. H.,Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2002, doi:10.1002/14356007.a22_399.

CrossRef - Sims, G. K.;Sommers, L.E.,Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 1986, 5, 503-509.

CrossRef - Sims, G. K.;Sommers, L. E.,J. Environmental Quality,1985, 14, 580-584.

CrossRef - https://www.alfa.com/en/catalog/A14012/.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/4-Methylpyridine.

- https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/4-Methylpyridine #section= Chemical-Vendors.

- Thomas, D. D.; Ridnour, L. A.; Isenberg, J. S.; Flores, S. W.; Switzer, C. H.; Donzelli, S.; Hussain, P.; Vecoli, C.; Paolocci, N.; Ambs, S.; Colton, C. A.; Harris, C. C.; Roberts, D. D.; Wink, D. A., Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2008, 45(1), 18-31.

CrossRef - Chen, P. R.; He, C.,Current Opinion in Chemical Biology, 2008, 12(2), 214-21.

CrossRef - Pennella, M. A.; Giedroc, D. P.,Biometals, 2005, 18(4), 413-28.

CrossRef - Cowan, J. A.; Bertini, I.; Gray, H. B.; Stiefel, E. I.; Valentine, J. S., Structure and Reactivity: Biological Inorganic Chemistry, 3, University Science Books, Sausalito,2007, 8(2): 175181.

- Jameel, A.;MSA, S. A. P., Asian Journal of Chemistry, 2010, 22(12), 3422-48.

- Anupama, B.; Sunuta, M.; Leela, D. S.; Ushaiah; Kumari, C. G.,Journal of Fluorescence, 2014, 24(4), 1067-76.

CrossRef - Singh, G.; Mangla, V.; Goyal, M.; Singla, K.; Rani, D., American International Journal of Research in Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics, 2014, 8(2), 131-136.

- Singh, G.; Mangla, V.; Goyal, M.; Singla, K.; Rani, D., American International Journal of Research in Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics, 2015,10(4),299-308.

- Singh, G.; Mangla, V.; Goyal, M.; Singla, K.; Rani, D., American International Journal of Research in Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics, 2015,11(2),158-166.

- Singh, G.; Mangla, V.; Goyal, M.; Singla, K.; Rani, D.; Kumar, R., American International Journal of Research in Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics, 2016, 16(1), 56-64.

- Singh, G.; Kumar, R., American International Journal of Research in Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics, 2018, 22(1), 01-08.

- Rani, D.; Singh, G.; Sharma, S., Oriental Journal of Chemistry, 2020, 36(6), 1096-1102.

CrossRef - Vogel, A. I., A Text Book of Quantitative Inorganic Analysis; John Wiley and Sons: New York, (Standard methods)1963.

CrossRef - Stamboliyska,B.A.;Binev, Y. I.; Radomirska, V. B.; Tsenov, J. A.; Juchnovskiet,I. N., Journal of Molecular Structure, 2000, 516, 237-245.

- Uno, T.;Machida, K.,Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan, 1962, 35(2),276-283.

- Heyn, B.; Hoffmann; Regina, Z. Chem.,1976, 16, 407.

CrossRef - Abramenko, V.L.;Sergienko, V.S.;Churakov, A.V.,Russian J. Coord. Chem., 2000, 26(12), 866-871.

- Abod, N. A.; M. AL-Askari; Saed, B. A., Basrah Journal of Science (C),2012, 30(1), 119-131.

- Mohan, J., Organic Spectroscopy: Principles and Applications, CRC Press, 2004.

- Barraclough, C. G.; Kew, D. J., Australian J. Chem., 1970, 23, 2387-2396.

CrossRef - Ward, B. G.; Stafford, F. E., Inorg. Chem.,1968, 7, 2569.

CrossRef - Toco’n, I. L.;Woolley, M.S.;Otero, J.C.;Marcos, J. I.,Journal of Molecular Structure, 1998, 470, 241-246.

CrossRef - Gupta, S. K.; Srivastava, T. S., J. Inorganic and Nuclear Chem., 1970, 32, 1611-1615.

CrossRef - Hossain, A. G. M. M.; Ogura, K., Indian J. Chem., 1996, 35A, 373-378.

- Brewerp,D. G.;Wong, P. T. T.;Sears, M. C.,Canadian J. Chem., 1968, 46(20), 3119-3128.

CrossRef - https://www.chemicalbook.com/SpectrumEN_123-56-8_1HNMR.htm.

- http://www.molbase.com/moldata/2973-spectrum.html.

- http://isotope.com/uploads/File/new_datachart.pdf.

- Pekmez, N. Ö.; Can, M.; Yildiza, A., Acta Chim. Slov., 2007, 54, 131-139.

- Wanga, X.;Heinemanna F. W.; Yangb, M.;Melcherc, B. U.;Feketec, M.;Mudringb, A. V.; Wasserscheidc, P.;Meyera, K., Supplementary Material (ESI) for Chemical Communications, The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2009.

- Kumari, N.; Sharma, M.; Das,, P.; Dutta, D. K., Applied Organomet. Chem., 2002, 16, 258-264.

CrossRef - https://www.chemicalbook.com/SpectrumEN_123-56-8_13CNMR.htm.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deuterated_DMSO#:~:text=Pure%20deuterated%20DMSO%20shows%20no,is%2039.52ppm%20(septet).

- https://www.chemicalbook.com/SpectrumEN_109-99-9_13cnmr.htm.

- https://sciencing.com/measure-zone-inhibition-6570610.html.

- http://www.sisweb.com/referenc/tools/exactmass.htm.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.